Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a painful condition affecting digestion and the large intestine. The development of IBS is complicated and was thought to be related to disruptions in the brain-gut connection, changes in gut motility, and stress. Recently, evidence has emerged that the gut microbiome may be involved. Scientists hypothesize that dysbiosis (a poor state of the gut microbiome) triggers the immune system which can lead to the development of IBS. There is evidence of post-infectious IBS that can develop after acute gastroenteritis or other infections, which supports this hypothesis. Further, distinct microbial profiles have been associated with IBS when compared to healthy controls, such as increased Firmicutes and decreased Bacteroidetes. Specific bacteria changes are also associated with the experience of and severity of symptoms. One study found that an increase in Cyanobacteria was associated with fullness, bloating, and an overall increase in GI symptoms, as measured with a GSCR-IBS score. The same study also reported that increased Proteobacteria was also associated with increased mental symptoms and a greater pain threshold.

Research on IBS and the microbiome is still evolving but is an exciting and interesting area of innovation. If you’re still curious about the role of the microbiome in IBS, please refer to our article, Symptoms of an IBS Attack, which covers symptoms, types, triggers, management strategies, and the multifactorial nature of the condition.

Foods To Avoid

There are some medications approved for the treatment of IBS, but placebo response rates to drugs have been high. Further, approximately 80% of adults with IBS report symptoms related to food intake and many individuals manage their IBS symptoms with dietary modifications.

Common Trigger Foods for IBS:

-

Highly Processed Foods: Processed foods, often laden with preservatives and artificial additives, can aggravate IBS symptoms. Reducing their intake may contribute to symptom management.

-

Food Allergies/Sensitivities (e.g. Gluten, Shellfish): Identifying and avoiding known food allergens, such as gluten and shellfish, is crucial for individuals with IBS, as these allergens can trigger adverse reactions and worsen symptoms.

-

Dairy (Milk, Cheese): Dairy products, particularly those with lactose, can be problematic for individuals with IBS. Exploring dairy alternatives or lactose-free options may be beneficial.

-

Spicy Foods: Spices can stimulate the digestive system and lead to increased discomfort for those with IBS. Moderating the consumption of spicy foods may contribute to symptom relief.

-

Gas-Producing Foods (Beans, Carbonated Drinks): Gas-producing foods, like beans, and carbonated drinks can contribute to bloating and discomfort. Limiting their intake can help manage IBS symptoms.

-

Sugar & Refined Flour: Foods high in sugar and refined flour may disrupt digestive processes and exacerbate IBS symptoms. Opting for alternatives with lower sugar content and whole grains can be beneficial. Do not swap these for 0 calorie sweeteners, however, as these tend to cause GI symptoms as they are unable to be digested (which is how they are 0 calorie!) and thus are fermented by microbes.

-

Excessive Caffeine: Excessive caffeine intake can act as a stimulant, potentially leading to heightened gastrointestinal activity. Monitoring and reducing caffeine consumption may be advisable. Keep your caffeine intake to less than 400 mg per day. For reference, an espresso shot contains 64 mg of caffeine while a Grande (16oz) cup of drip coffee from Starbucks contains 330 mg of caffeine.

-

Too Much Protein: Overconsumption of protein, particularly from certain sources, can contribute to digestive issues. Aim for 2-3 servings of protein or 50g of protein per day. Choosing easier-to-digest proteins, such as eggs, chicken, turkey, fish, extra-firm tofu, and plain lactose-free greek yogurt can be easier on your digestive system.

-

Fried Foods: Fried foods, high in fats, can be harder to digest and may contribute to IBS symptoms. Choosing alternative cooking methods like baking or grilling may be more suitable.

By being mindful of your intake of these potential triggers, you can start taking proactive steps toward managing your symptoms of IBS and improving your overall quality of life.

Foods To Adopt

Low FODMAP Diet

One of the most widely used dietary changes is adopting a low FODMAP diet. FODMAP stands for Fermentable, oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols and refers to groups of food that should be avoided for optimal dietary IBS management. In the early 2000’s, FODMAP was coined to describe poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrates and sugar alcohols which are unabsorbed by the GI tract or indigestible, leading to digestive symptoms. Research has connected a low-FODMAP diet with various organisms in the microbiome including Bifidobacterium, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroides. The goal of a low FODMAP diet is to reduce the ingestion of these carbohydrates and ultimately reduce gas production (which causes abdominal pain, bloating, excessive gas, and cramping.

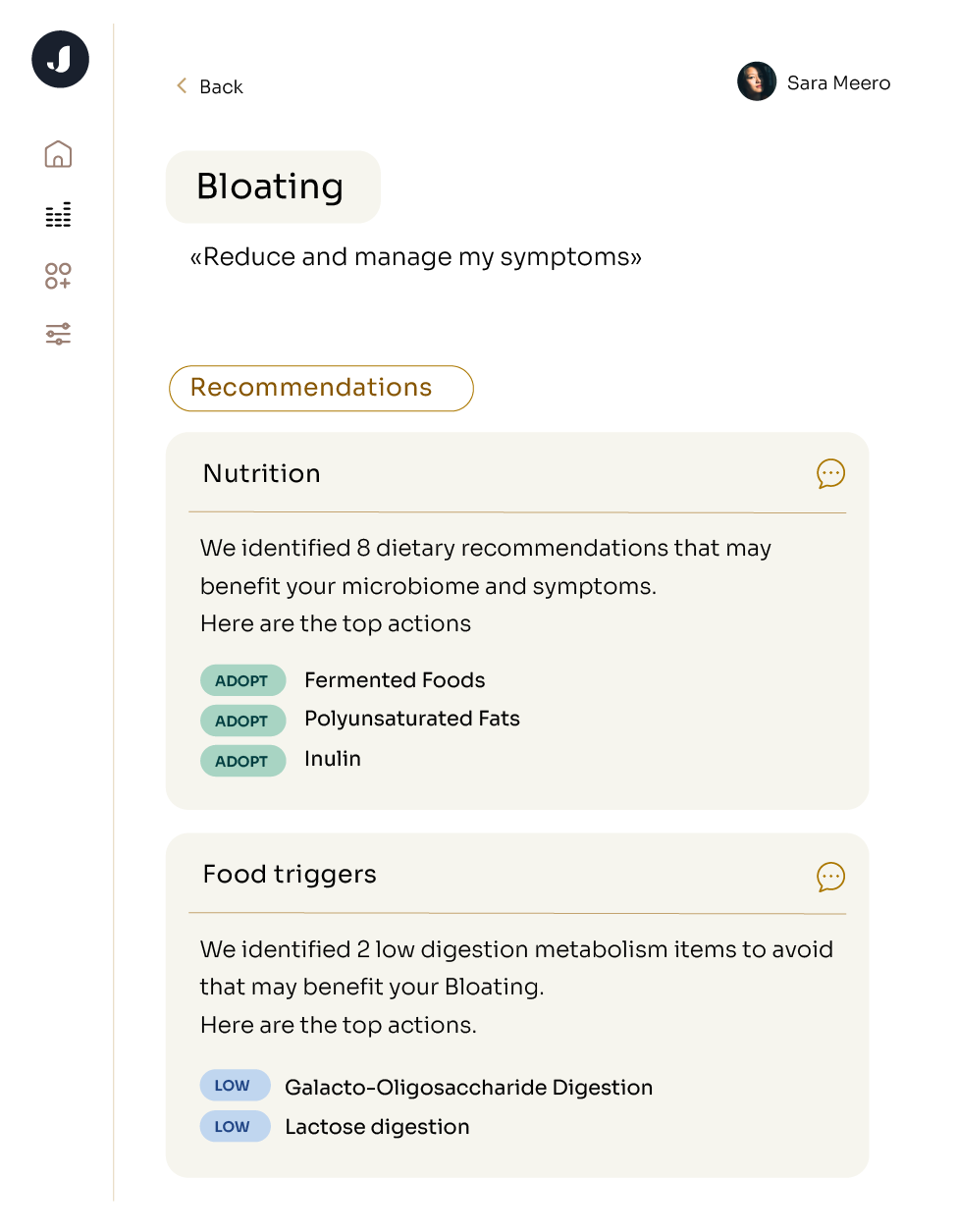

It is important to note that ingesting high FODMAP foods is not the cause of IBS but rather, an instigator and perpetuator of IBS symptoms. Additionally, people with IBS do not necessarily react to all the FODMAP foods, so understanding how FODMAPs relate to the microbiome and having your own microbiome profiled, may assist you in identifying which groups may trigger your symptoms. A low FODMAP diet should only be followed for a short period of time (4-6 weeks), then followed by the re-introduction of FODMAP foods to determine your own personal tolerance to each food and maintain adequate nutrient intake. Please consult a healthcare professional when implementing this diet.

The different members of the FODMAP group are described in more detail below:

Fermentable refers to a metabolic process by gut microbes whereby they break down undigested carbohydrates in the large intestine, resulting in the production of gas.

Oligosaccharides consist of fructo-oligosaccharides and galacto-oligosaccharides, which are indigestible by all humans and are fermented by our gut microbes.

Disaccharides are simple sugars such as lactose, which is composed of two sugar bases, glucose and galactose, and is a sugar mainly found in dairy products. In individuals with lactose intolerance, lactose remains undigested until fermented by gut microbes.

Monosaccharides are simple sugars such as fructose, which exists on its own and is similar to glucose but is poorly absorbed by the body, leading to fermentation.

Polyol: also known as “sugar alcohols” and refers to any ingredient ending in “-ol” such as sorbitol, maltitol, or erythritol, and is poorly absorbed, leading to fermentation.

How to Replace FODMAPs

Other Dietary Interventions

Probiotics

Gut microbiota may differ in people suffering from IBS compared with healthy individuals. Probiotics may improve quality of life in IBS. The World Gastroenterology organization reports in IBS that “[a] reduction in abdominal bloating and flatulence as a result of probiotic treatments is a consistent finding in published studies; some strains may ameliorate pain and provide global relief. The literature suggests that certain probiotics may alleviate symptoms and improve the quality of life in patients with functional abdominal pain.” They recommend probiotics such as Bifidobacterium infantis 35624, Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745, or others which can be found on pages 19-20 here.

Digestive Enzymes

Some small studies suggest that digestive enzyme supplements may help alleviate IBS symptoms. The idea is to replace enzymes that may be lacking or reduced in the digestive system of a patient with IBS, which should then help break the bonds linking the short-chain carbohydrates before it reaches the large intestine. Again, it’s important to remember that studies on this are limited, so speak with a healthcare provider before supplementing with this.