The microbiome refers to all of the microorganisms, and their genetic material, present at various sites in our bodies. We're focused here on the gut microbiota, which are probably the most important for human health, but there's also the skin microbiome, the oral microbiome, the respiratory tract microbiome, and more.

I usually like to give examples of certain bacteria that everybody knows about, like Lactobacillus. It’s a probiotic that is known to have beneficial roles in digestion and immunity. Another organism that we just mentioned is Clostridioides difficile, which can cause diarrheal diseases. So gut bacteria can play a role both beneficial and also harmful.

We know that the gut microbiota has an enormous role in human health and disease. I actually think we're just really scratching the surface of what we understand about it. And we're also at the same time developing novel ways of approaching understanding the genetic material of the entire microbial community. This is really an area of explosion in bioinformatics research. To illustrate that point - we also know that the gut microbiome inside our bodies can also play a role in microbiome at other sites, too. The skin microbiome can also be tightly tied to what's going on in the gut microbiota. We’re beginning to understand how these systems interact.

When we describe microbes, we often break them down at the genus level. Let’s take E. coli for example. That E part stands for Escherichia, which is the genus. The genus helps us understand general characteristics, potential functions, and other general roles of that organism within the microbiome.

However, the genus doesn’t always give enough information. For example, we could talk about one important diarrheal disease, Clostridioides difficile. Not all Clostridia are created equal, and difficile is particularly a bad one, so there are instances where understanding the specific species is critically important.

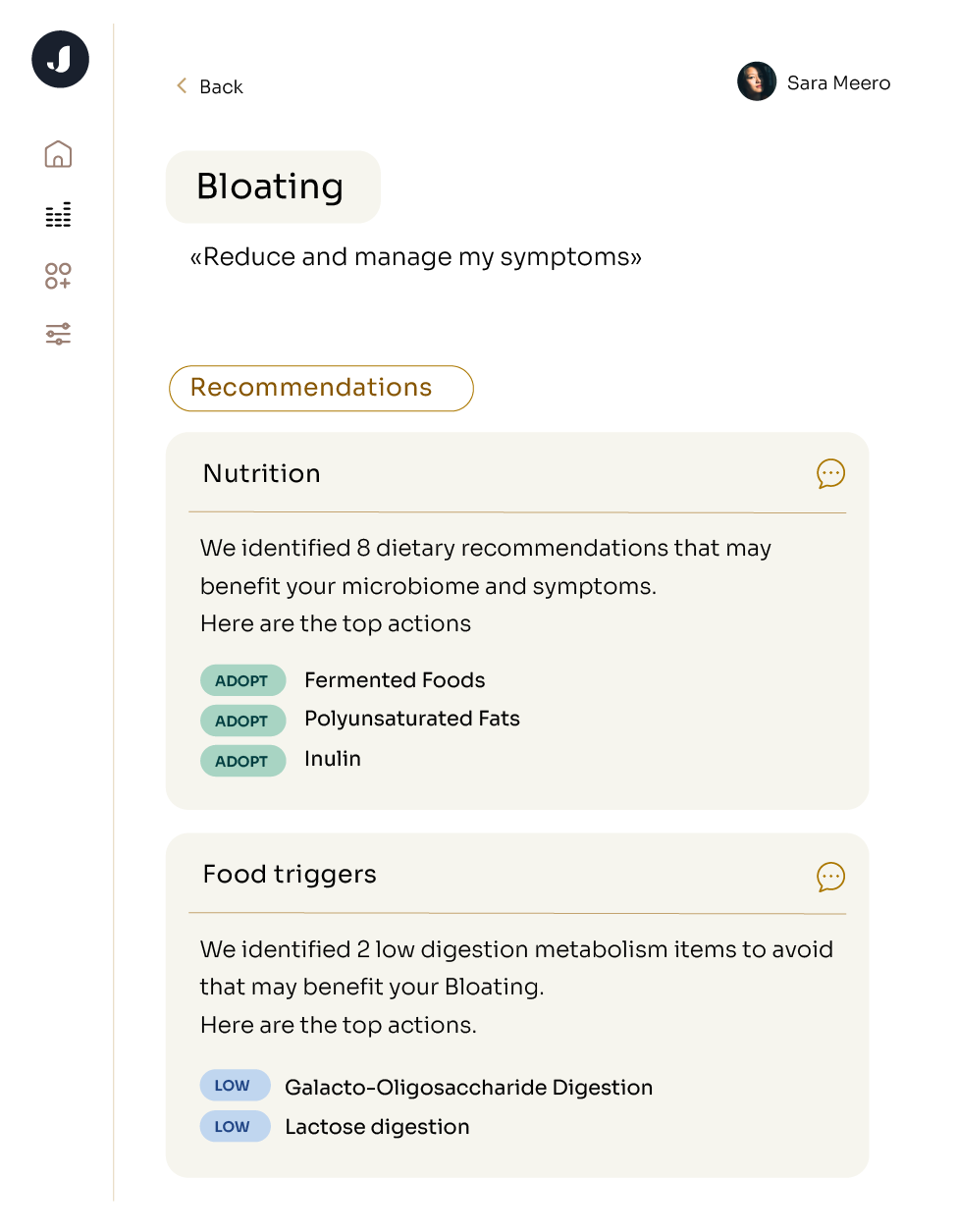

So this is a challenging question. We’re still learning about it. And actually, that's one of the reasons why I like Jona - because it's tied to evidence-based research. This is one area where technology and this product has really helped. It's not just providing a bunch of testimonials from naturopaths. It's providing evidence in the literature about specific types of microbes and their direct role in human health using what's been published in peer-reviewed journals.

Whenever I'm assessing readouts from microbiome analyses, it's important to remember that while certain organisms are associated with health or disease states, it’s not always so clear-cut. The reality is everybody is a little bit different. There may be people who have a host of GI symptoms and diseases, and their microbiomes may look “healthy.” Of course, there are things that we could do to upregulate microbes that we associate with healthier living and less disease states. But, everyone's microbiota isn't going to look the same. That's why it's actually important to not focus on one thing or one group of bacteria - what's important is seeing your microbiome in the context of the whole body, including how we’re feeling and what diseases we may have.

As someone who does research in the gut microbiome and its role in human health, there are certain types of genus level that I do look at when I'm interpreting someone's microbiota. Those include things like Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, E. coli strains, Clostridioides, Firmicutes, Staphylococcus, even things like Akkermansia and Ruminococcus. The reasons I look at these in particular is because they've been associated in various levels with human diseases.

Now, again, everyone's a little bit different, right? So someone could have high levels of Staphylococcus, but actually be completely fine. Context is everything. When we look at these studies, we're looking at not only the types of microbes that are there, but also their relative abundance. How abundant are they in comparison to the other microbes that are there? In some ways, it's actually that relative abundance that's more important than just the presence of a specific microbe.

Let’s take Ruminococcus for example - it’s a type of microbe that has been associated in high abundance with what we would consider a healthier gut microbiome. That’s because in inflammatory diseases of the gut, we've seen low levels of Ruminococcus, which has been replicated in multiple studies. So again, its presence in the gut is good, but you want to make sure it’s also strong in relative abundance.

I look at these [organisms] in particular is because they've been associated in various levels with human diseases.

So, what's important to know is that we are covered in microbes inside and out. Our gut, our skin - it’s all covered in microbes, and some of these we might classify as pathogens. It really depends on the relative abundance of these bacteria. I’m an inflammatory bowel disease specialist, so very often, I'll see patients who may have diarrheal diseases or other inflammatory diseases of the gut. Sometimes we pick up on microbes that could be pathogenic through diagnostic testing such as Jona. But it's important to understand the abundance of these organisms in the gut, what symptoms are currently present, and whether this is something that really is causing how the patient is feeling. There’s many subtypes of E. coli that can be associated with acute gastroenteritis or diarrheal disease, but many healthy patients walking around might also have E. coli living inside their gut. It’s not always a bad thing. That's why it's important to evaluate these things with clinical guidance.

Of course, there are certain microbes out there, such as Salmonella or Campylobacter jejuni that we know are pathogenic and ought not to be in the gut. Same for certain types of parasites like Entamoeba and Giardia. When those pathogens are in high abundance, that's when they tend to cause more symptomatic human disease.

Changes in the gut microbiome can happen very rapidly. An antibiotic is a perfect example of that. Antibiotics can be important for tackling infection, but they can be incredibly dysbiotic to the gut microbiota. Historically, we’ve seen doctors prescribe antibiotics when we're not sure what we're treating, or it may be targeting something that is not bacterial in origin. I think we’ve recognized this in Western medicine and moved toward antibiotic stewardship, or being conscious of the impact of antibiotics on the body.

Diet can also change the microbiome, but the changes from diet tend not to be as rapid. Patients often come to me with symptoms, and we'll talk about dietary modifications that may help with those symptoms due to changes in the gut microbiota. And those changes don't happen overnight. So it's really more about modifying diet and sticking with that modification for a period of weeks to see clinical changes.