Gluten intolerance, also known as non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), occurs when individuals experience adverse reactions to gluten containing grains; predominantly wheat, barley and rye. Unlike celiac disease, gluten intolerance does not involve an autoimmune response or damage to the small intestine. It results from intolerance of the complex carbohydrates present in these foods. Regardless of the cause, gluten intolerance can still cause significant discomfort and affect overall health.

Recognizing the early signs of gluten intolerance can help in seeking timely intervention. Common initial indicators include bloating and gas, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, fatigue, or headaches (gluten intolerance can look different in different people). Gluten intolerance might occur with symptoms even beyond the digestive tract, including joint pain, brain fog, mood changes, skin rashes or eczema. It can help to keep a food journal so that you see any patterns between foods that cause your symptoms and whether gluten might be to blame.

Both conditions involve adverse reactions to gluten containing foods, but they differ significantly in their underlying mechanisms and impact on the body. Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder where ingestion of gluten leads to damage in the small intestine. Celiac disease is diagnosed through blood tests and a biopsy (a small tissue sample that a pathologist looks at under a microscope). Gluten intolerance does not cause such damage and is typically diagnosed based on symptom relief after gluten removal and exclusion of celiac disease and wheat allergy.

Celiac disease is particularly notable for its long-term consequences. Over time, the lining of the intestines of someone with celiac disease become worn down and they fail to take up nutrients properly. This intestinal wear can also lead to additional complications such as vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

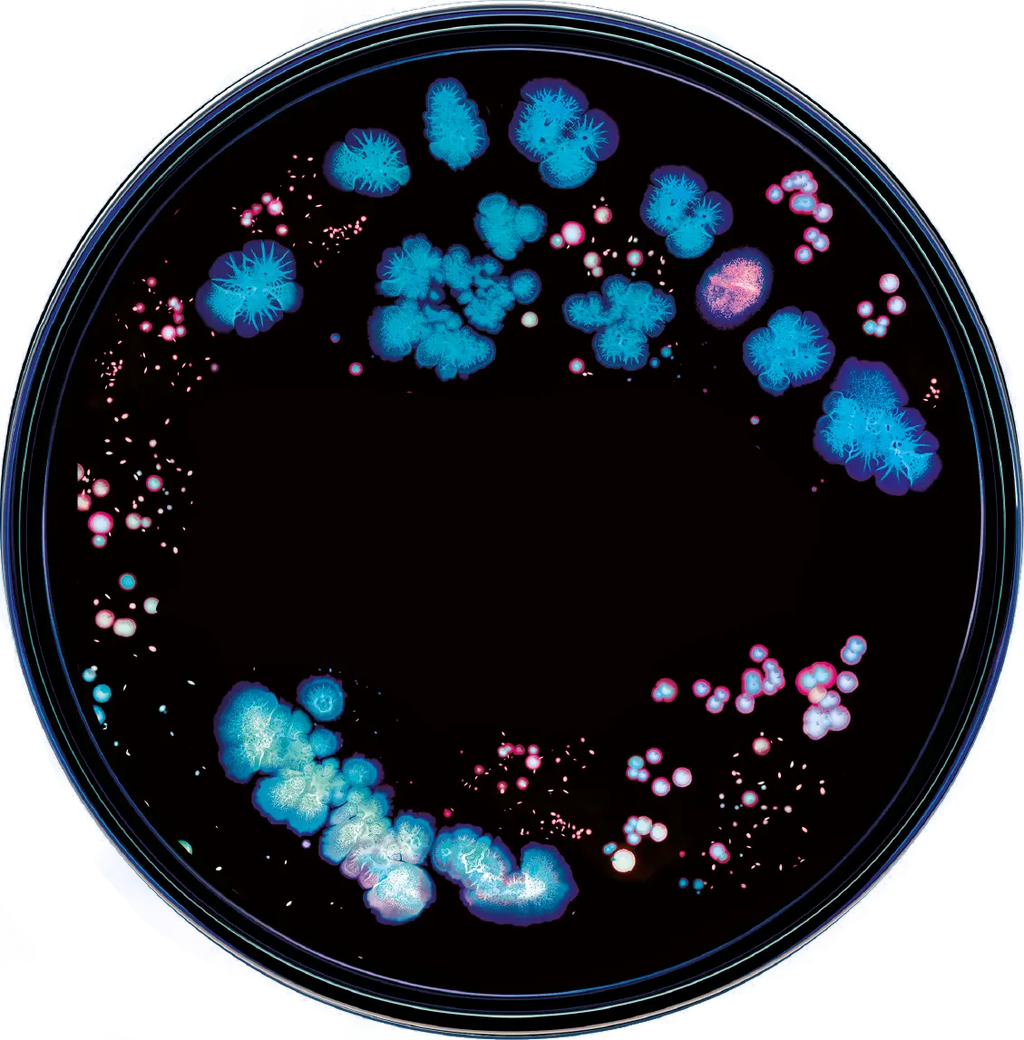

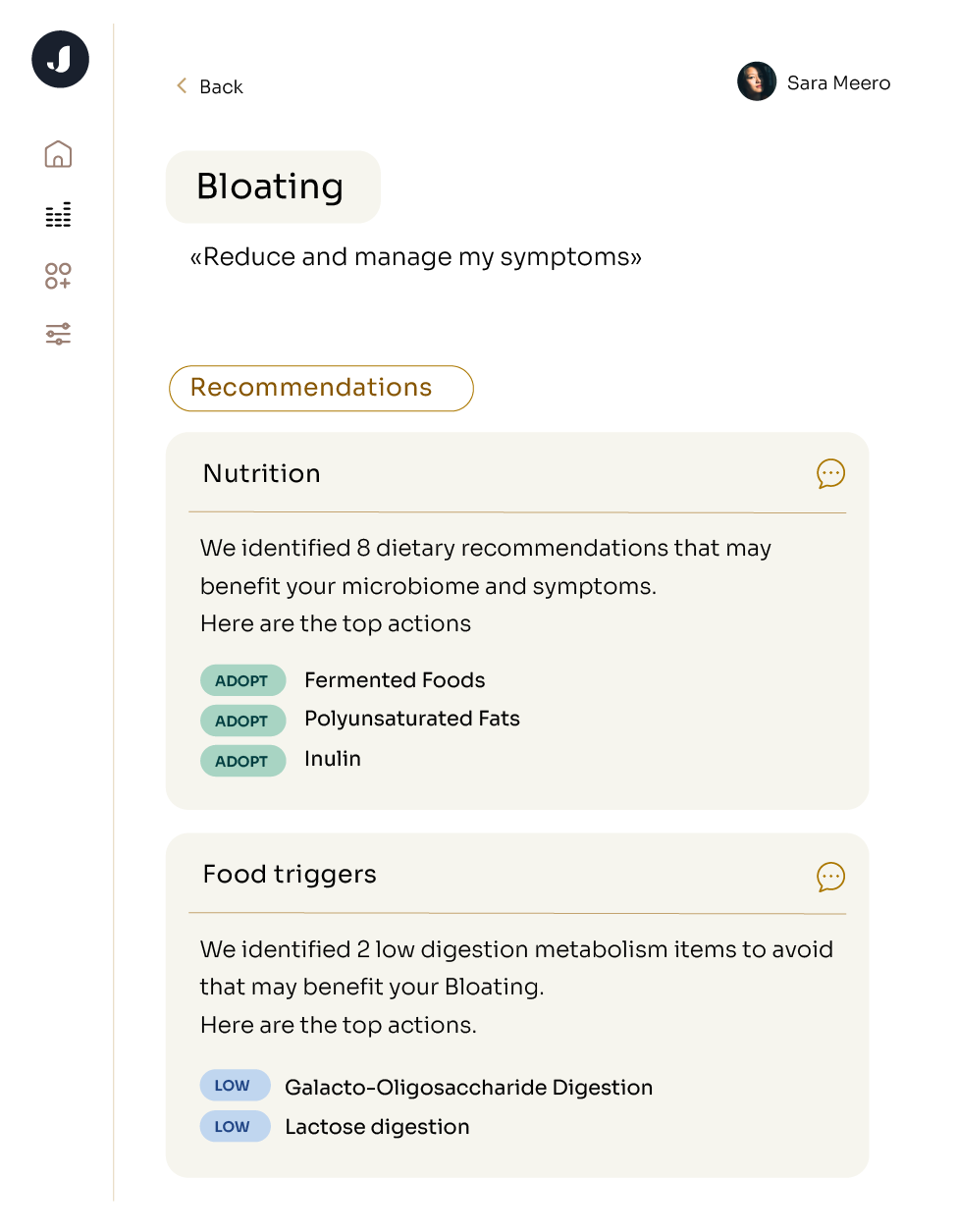

Assessment of gluten intolerance can begin with a microbiome test to see if you have microbes capable of digesting the carbohydrates in gluten containing grains. Jona’s microbiome profiling assesses your gut for gluten intolerance by analyzing your microbiome signature. After you’ve understood the capabilities of your microbiome, you can confirm gluten intolerance via elimination and observation. You’ll start by removing gluten from the diet for a few weeks to see if symptoms improve. This process might involve a food diary or a log of your symptoms. Then, you can try reintroducing gluten to your diet little by little. Tracking how you feel and analyzing this with a doctor can help make sense of what level of exposure triggers what type of symptom.

Although there is no known cure for gluten intolerance, the condition can be managed effectively through dietary adjustments and lifestyle changes, including a strict gluten-free diet and dietary supplementation with vitamins and minerals if you are worried about lower nutrient absorption.

Unfortunately, avoiding gluten requires more than just avoiding wheat. Gluten can hide in barley, rye, triticale, malt, and brewer’s yeast, so some less common foods to avoid on a gluten-free diet include beer, many packaged snacks and malt vinegar.

Several conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, lactose intolerance, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and fructose malabsorption can all mimic gluten intolerance, which is part of the reason that testing your microbiome and speaking with a doctor can be critical.

It may take a few days to weeks for gluten to be fully cleared and symptoms to subside. The exact duration depends on individual metabolism, the severity of intolerance and adherence to a gluten-free diet.

Symptoms of gluten intolerance can appear within hours to a few days after consuming gluten.

To expedite the removal of gluten and alleviate symptoms, drink plenty of water, stick to foods that definitely don’t contain gluten, like fruits and vegetables, and be sure to rest - giving your body time to recuperate can avoid making your symptoms any worse.