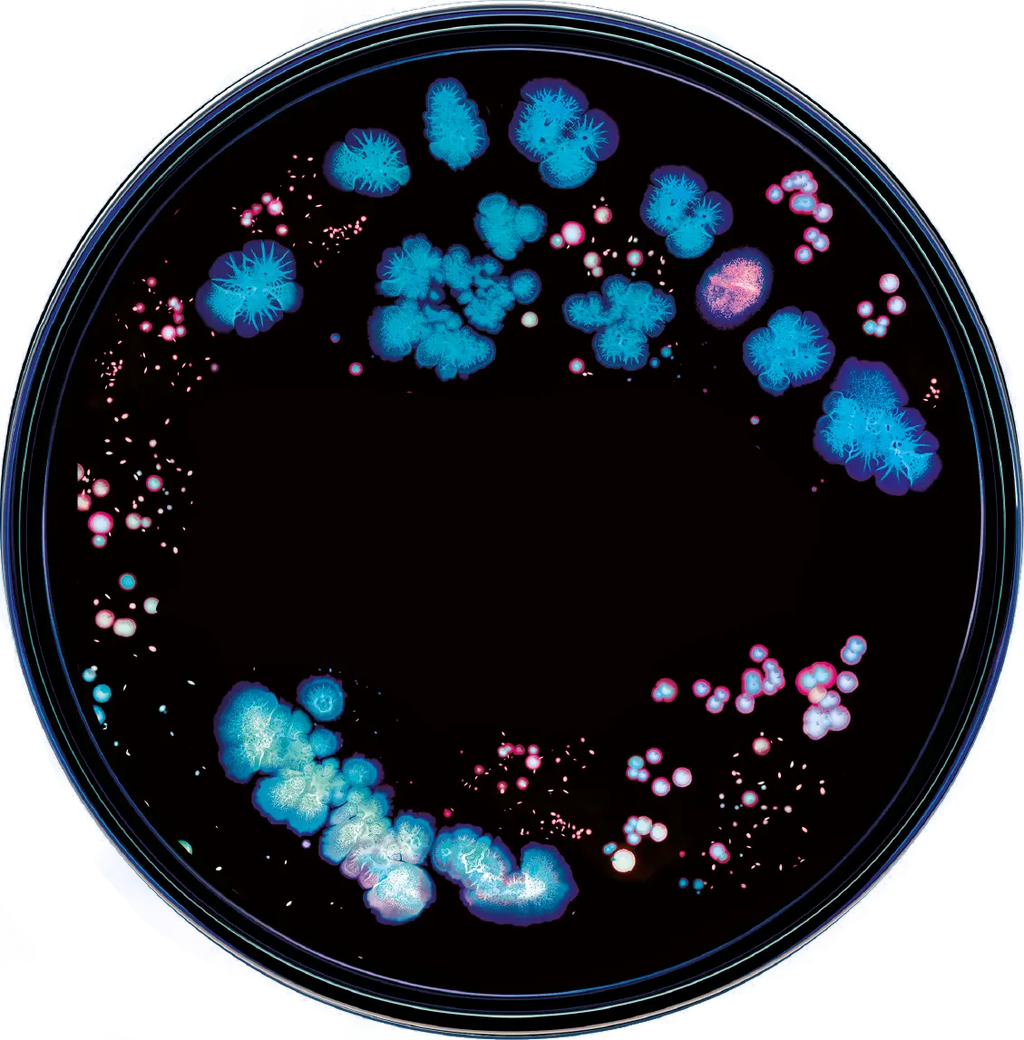

The term human microbiome refers to the collection of all microorganisms (bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and more) plus the host environment. In particular, the term comprises the genomes of all the microorganisms. A genome is the complete set of genetic material (DNA) inside a living organism. In the context of human health, the human microbiomes can be distinguished for various parts of the body, including the gut, skin, mouth, and more; each local microbiome encompasses all the genetic material of the microorganisms residing as well as host and environmental factors. Think of the different regions of your body as different microbial climates: some are hot and dry, others are cooler or more damp. Some have oxygen and some do not. Each of these environments suits some bacteria more than others, which is one factor shaping the diversity of microbes in and on your body.

Microbiota refers to the community of microorganisms themselves that inhabit a specific environment. When we talk about the gut microbiota, for instance, we are referring to the bacteria, viruses, fungi and other microbes residing in the gastrointestinal tract. These organisms coexist in a delicate balance, contributing to the host's health by breaking down certain carbohydrates, producing vitamins and modulating the immune system.

The organisms that make up your microbiota actually match your human cells 1 to 1. However, because these organisms are so small in comparison to a human cell, their total weight comes to only a few pounds.

The microbiome plays a pivotal role in human health. It is involved in:

- Digestive Health: Microbes aid in the digestion of food, the synthesis of vitamins, and the absorption of nutrients. For example, the bacteria in your gut break down the fiber that you eat and turn it into short-chain fatty acids.

- Immune Function: The microbiome helps train and modulate the immune system, protecting against pathogens. More than 90% of your immune cells are located in the gut.

- Metabolic Health: Gut microbes influence metabolism, energy balance, and fat storage, with obesity and other metabolic conditions having clear reflections in the distribution of gut bacteria.

- Mental Health: Emerging research links the gut microbiome to brain function and mental health along the gut-brain axis.

- Skin Health: Increasing research is showing how the gut microbiome affects skin health

- Athletic Performance: A wide range of studies have examined how the microbiome impacts athletic performance, opening new avenues for diet optimization to enhance performance and methods to avoid the gut issues that are common among athletes

Disease Prevention: An imbalanced microbiome (dysbiosis) is associated with various conditions, including obesity, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and even certain cancers. Evidence is emerging for a causal role of the gut microbiome in diseases ranging from gallbladder inflammation to certain cancers.

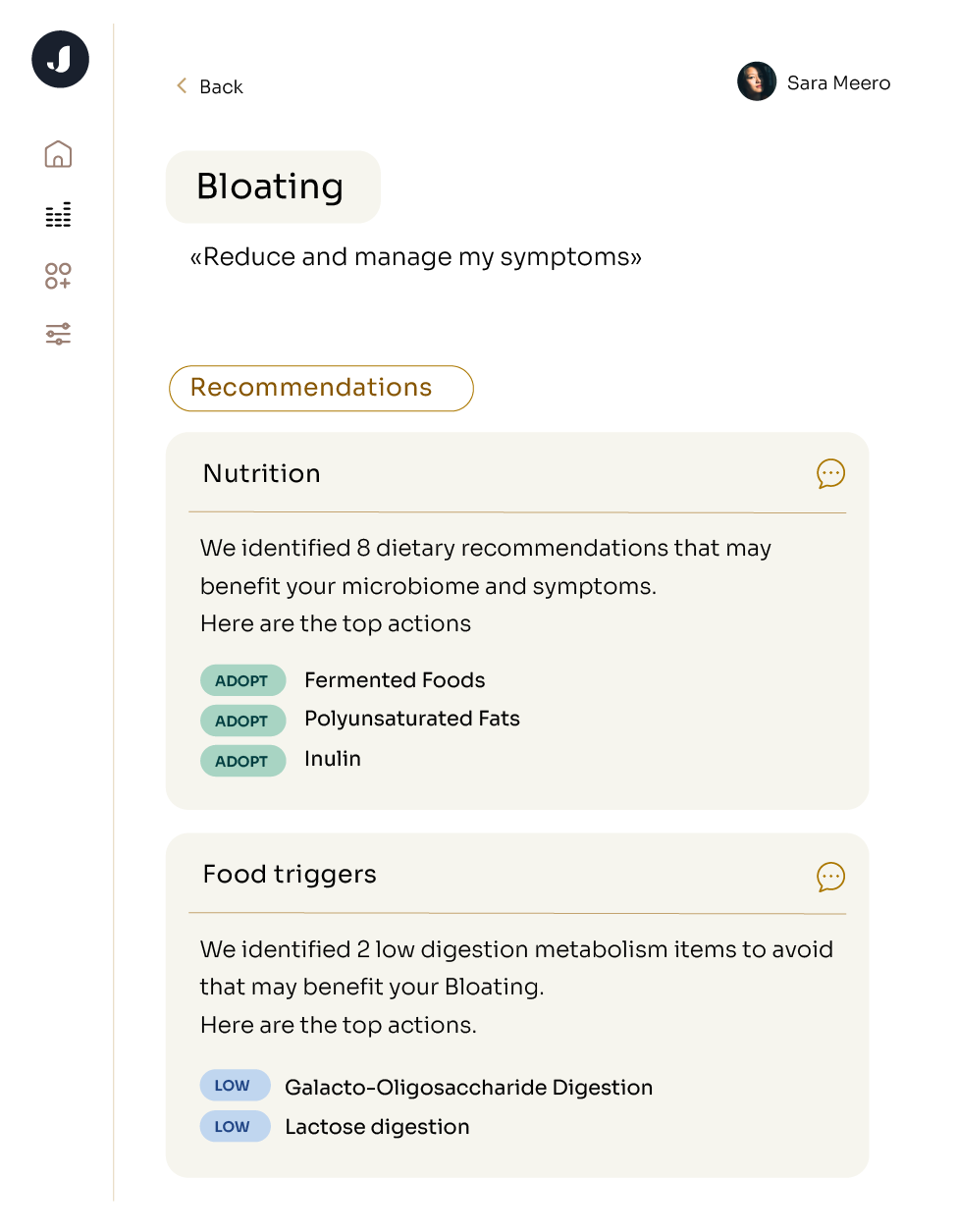

Microbiome analysis is used to assess and understand many GI complaints. Your doctor might order microbiome testing to look for specific pathogens like E. coli or C. difficile. Microbiome testing can also be a tool for you to take control of your own health. In recent years, direct-to-consumer tests for the gut microbiome have seen enormous growth as people want to better understand their health and take action to improve. With genetic sequencing becoming faster and cheaper than ever before, consumers can benefit from the deeper layer of information offered by shotgun metagenomic sequencing.

The distinction between microbiome and microbiota helps discuss how we sequence the organisms in a sample. Microbiome analysis involves studying the composition and function of microbial communities within a specific environment. The goal is to isolate the DNA from each microbe and then match it to a database of known organisms to understand the diversity of microbes that are present and their abundance.

If you’ve already profiled your microbiome through Jona, you’re familiar with this process: you use a small brush to collect a stool sample and place this sample into a vial of solution. This vial is then sent to the lab for sequencing, and a few weeks later, you’ll receive your report. But what happens in the middle?

When you collect a stool sample, you only need a tiny amount of material because it is so dense with microbes. A gram of stool (about a quarter of a teaspoon) can contain 20 billion organisms from your gut. The liquid in your Jona kit is a buffer which helps to transport the stool in a stable state, inactivating most bacteria and preventing degradation of the to-be-analyzed bacterial DNA.

Upon arrival at the lab, the sample will be lysed. Lysing means breaking open the microorganisms to access their DNA, which is stored in long chains inside them. Lysing can be done with a chemical that dissolves the bacterial membranes, or physically with a process called bead-beating, in which the sample is shaken with small beads. Once the cells are broken open, it’s possible to sequence the microbes’ genetic material in different ways. We’ll cover that in the next section.

Many stool tests use a specific marker gene, called the 16S rRNA gene (“16S sequencing). This gene encodes part of the fundamental machinery of life, the ribosome, and all bacteria have it. Because this gene is so crucial, it evolves slowly. This is an opportunity to, therefore, distinguish lineages of different bacteria only based upon this particular marker region, i.e. without using their entire genomes for comparison. The technique came about in the 1970s as a way of distinguishing microbes with limited sequencing power, as the 16S gene has only 1,500 base pairs - an amount that was gigantic in the early days of genetic sequencing, but trivial today. However, 16S is only capable of identifying bacteria (fungi have a different ribosome) and often cannot resolve differences between species or strains.

Metagenomic shotgun sequencing was developed after 16S with major advantages. First, it looks at an organism’s whole genome, not just one gene. In the event that an organism is unidentified, metagenomic shotgun sequencing offers more clues to help determine its relatives than 16S. For microbiome research and disease applications, metagenomic shotgun sequencing offers a broad, high-resolution view into the full set of organisms in a sample. Metagenomic shotgun sequencing is able to measure all DNA in your sample, and thus detect all microorganisms in your gut, not just bacteria, and can be used to differentiate between species and strains. Furthermore, by sequencing the whole DNA, shotgun metagenomic sequencing allows us to examine genes of microbes that could affect your health, for example virulence factors or antibiotic resistances. Metagenomics also help us understand better how your microbiome is interacting with different metabolic pathways. This is the sequencing method that Jona uses, and it’s what enables us to draw rich information from individual microbiome results and tie them to the literature.