Your skin serves many vital functions, including protecting against infections, supporting immune health and regulating inflammation. While the definition of healthy skin can vary from person to person, all skin consists of three layers: the epidermis, dermis and hypodermis. The main layer of our skin is the dermis, where most of the living cells exist. The epidermis is composed of layers of dead cells, which have been sloughed off from the dermis. The hypodermis sits underneath the dermis and is the layer populated by all the blood vessels and nerves.

Unlike your gut lining which must allow for passage of nutrients, a key role of your skin is its barrier function, which safeguards the hypodermis from pathogens and harmful chemicals. Damage to any of these layers can lead to decreased barrier function and overall damaged skin. Our skin also helps regulate body temperature through glandular control mechanisms and allows us to interact with our environment through sensation and touch working with our nervous system to detect pressure, pain and temperature.

Building on our previous discussion of the gut-brain axis in the Jona Journal Blog, we now explore the gut-skin axis. The gut microbiome has a significant impact on signaling processes throughout the body, playing a crucial role in skin health by maintaining epidermal differentiation and overall skin homeostasis via microbe produced metabolites. Commensal bacteria that normally reside in the GI tract such as Lactobacillus, can drive skin allostasis, controlling T-cell differentiation. Scientists have identified the mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway, which serves as a signaling system within cells that interacts with gut microbes. Gut microbiota can influence the development of skin conditions, such as acne, through their interactions with the mTOR pathway. Regulatory metabolites produced by gut microbiota mediate functions within this mTOR pathway such as cell proliferation and lipid metabolism, while the pathway itself can also shape the composition of the intestinal microbiota by regulating the intestinal barrier. This creates a feedback loop where inflammation arises, contributing to skin diseases like acne and eczema, with inflammation serving as a key proponent. This pathway can also be activated by factors like a high glycemic load, leading to inflammation that affects both epidermal and intestinal health through microbial interactions.

As we transition into the drier months of fall and winter, moisture—a cornerstone of healthy skin—begins to fade. To protect your skin’s barrier function, using thicker moisturizers can effectively replenish lost hydration. Skincare doesn't necessarily mean trying an array of expensive products that all claim to serve different purposes for your skin and solve problems you didn't even know you had. This season, focusing on seasonal eating is essential for obtaining the nutrients that support both gut and skin health. Our bodies have evolved to adapt to the cycles of seasons that coincide with harvests. This adaptation helps align our bodies with the metabolic efficiencies that developed due to the utilization of foods that are naturally available at certain times of the year. The amount and types of nutrients can selectively grow certain bacteria like SCFA-producers, and generate different metabolites, those which have positive effects on the gut epithelium and the mucosal immune system. Autumn brings an array of fruits like apples and bananas, alongside vegetables such as brussels sprouts and carrots, all at their peak freshness and nutrient density. As the seasons shift, many foods that become available at their freshness peak in autumn transition from having a trend of being rich in Omega-3 to Omega-6 fats—think nuts and seeds. These Omega-6 storage fats can slow metabolism, allowing us to thrive on less food as we gear up for the winter months and the “hibernation” period ahead. This balance between Omega-3 and Omega-6 fatty acids has been shown in mice to keep inflammation status at a normal level by lowering levels of pro-inflammatory bacterial groups such as Proteobacteria, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Clostridium and increasing anti-inflammatory bacteria such as Bifidobacterium, Akkermansia muciniphila, Lactobacillus (primarily L. gasseri), Clostridium clusters IV and XIVa, and Enterococcus faecium.

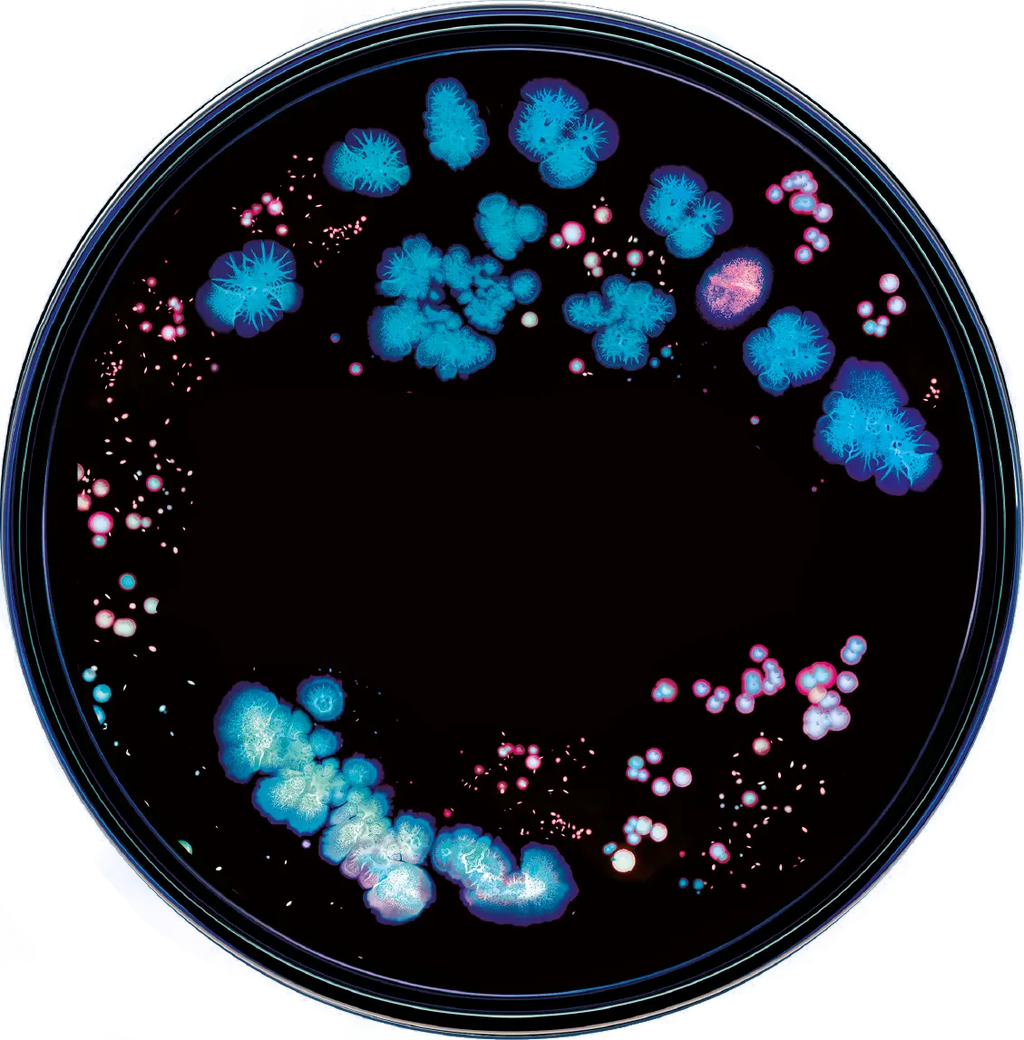

Dysbiosis in the gut is linked to 3 common skin disorders, among many: Psoriasis, Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema) and Acne.

Acne is the most common skin condition in the Western world, drawing significant attention in both research and personal care. When examining the microbiome, we focus heavily on the gastrointestinal tract, the body’s largest sensory organ, and its implications for skin health. Notably, for over 100 years, scientists have suggested that individuals with acne exhibit increased permeability of the gastrointestinal tract, which may influence skin conditions. People who have acne tend to lack strains of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria. – those that produce short-chain-fatty-acids (SCFAs) that help maintain a healthy gut barrier. Research highlights the crucial role of this pathway in maintaining the epidermal barrier, showing that individuals with elevated expression levels of mTOR are often found among people with acne.

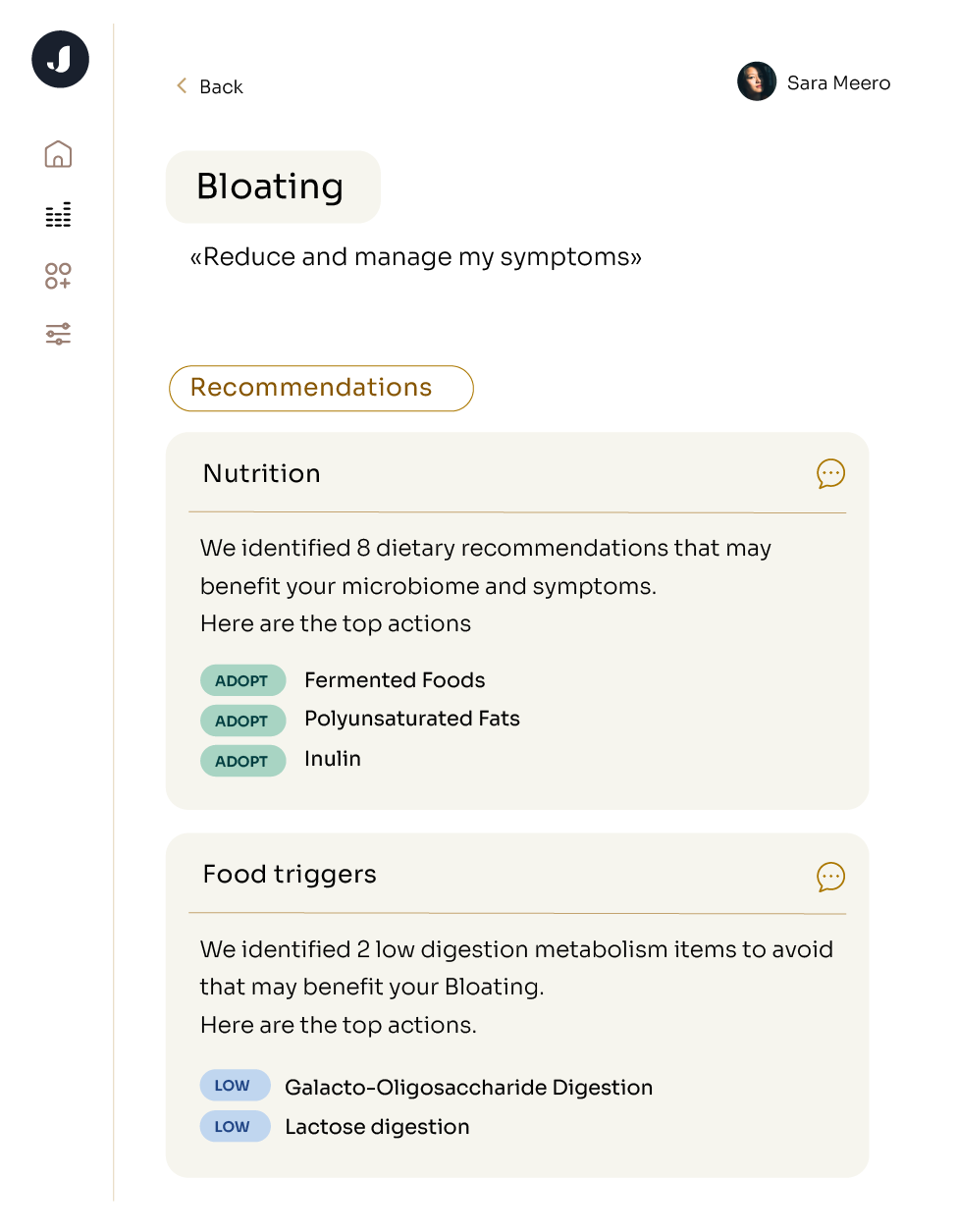

Shifts in specific microbial communities, such as drops in SCFA-producing bacteria, can trigger immunologic reactions, leading to the development of acne. However, individual alterations in lifestyle and diet that can be customized to each individual's unique microbiome in order to increase SCFA producing bacteria and lower inflammation, therefore lowering likelihood of skin-related conditions. At Jona, we can provide you with the insights needed to tailor these measures for your specific skin health needs.

Psoriasis is a common skin condition thought to be caused by an immune issue that results in skin cells growing faster than normal, where infection-fighting cells attack healthy skin cells. It’s characterized by itchy, red, scaly patches and the effects of Psoriasis extend far beyond the skin, triggering inflammation that can impact multiple body systems, including cardiovascular, musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal systems. Experts believe that ultraviolet light hinders the rapid growth of skin cells, a hallmark of psoriasis, which can help manage symptoms. Research indicates a strong link between gut bacteria—like Eubacterium fissicatena and Lactococcus bacterial groups and Actinomycetales—and psoriasis; higher concentrations of these bacteria are associated with the disease and can worsen symptoms by escalating inflammation and altering immune responses, leading to complications such as atherosclerosis. Additionally, many individuals experience joint pain due to Psoriatic Arthritis, commonly occuring with Psoriasis, highlighting the interconnectedness of skin and joint inflammation. Interestingly, the genetic material of gut bacteria has been identified in plasma samples of patients with psoriasis. Recognizing these broader implications emphasizes the importance of managing gut health and inflammation to improve overall outcomes for those living with psoriasis.

The connection between the microbiome and atopic eczema, reveals some surprising truths. Research shows that individuals with eczema often have a less diverse range of bacteria on their skin and in their gut, particularly a lower level of bacteria like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. As we now know, the health of our gut is closely tied to skin conditions; the large intestine plays a key role in regulating inflammation and immune responses, directly impacting the severity of eczema flare-ups, mostly because dermatologists claim that individuals with eczema tend have have an overactive immune system thats responds to irritants or allergens by producing inflammation. Flare-ups of eczema can manifest as red, itchy patches of skin that may become dry, cracked or even oozing. These areas are often accompanied by intense itching, leading to scratching that can further irritate the skin and exacerbate the condition. Over time, the affected skin may thicken—a process known as lichenification—as the body attempts to protect itself. While eczema triggers are as unique as the individuals experiencing them, there are ways to prepare for the change of seasons. Flare-ups can be triggered by various factors, including stress, weather changes and certain foods, making the experience not only uncomfortable but also unpredictable. For instance, as temperatures drop in the fall, lower humidity can lead to drier skin, making individuals more susceptible to irritation. This intricate relationship suggests that analyzing your gut health for signs of eczema and making changes to address these signs may be key strategies in managing eczema symptoms effectively.