How does exercise affect our microbiome?

Exercise is an essential part of maintaining overall health. Moderate exercise improves fitness and body composition but also has been proven to help reduce inflammation, strengthen the immune system, and improve digestion. Improved digestion refers to reduced stool transit time (or going to the bathroom more frequently) and thus reduces the time that the gut is exposed to harmful bacteria in the stool. Beyond this, exercise also greatly influences the exact balance and profile of the microbiome.

Researchers have studied the effects of exercise on the microbiome by studying elite athletes and highly fit individuals and comparing them to sedentary people. One study found that VO2 max, a measure of cardio fitness, positively correlates with a key indicator of gut health, solidifying that fitness influences the microbiome. Moderate exercise has been shown to enrich microflora diversity which is associated with an improvement in health status and increased longevity. This microbial diversity includes a decrease in pathogenic, meaning disease-causing, bacteria like Escherichia Coli and an increase in beneficial health-promoting bacterial species within families such as Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae that produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). SCFAs, namely butyrate, propionate, and acetate, are very important to exercise and gut health. They can provide energy to muscle cells, to intestinal cells, are anti-inflammatory, and can strengthen the gut barrier, preventing the entry of harmful substances into the bloodstream. Interestingly, one study on Boston Marathon runners found a specific increase in Veillonella after running the race. This bacteria metabolizes lactic acid, which is produced during strenuous exercise and causes muscle soreness, to propionate, which is an SCFA, presumably to use it for energy production. Another study compared the microbiomes of women who exercised the amount recommended by the World Health Organization with women who were sedentary. After only 7 days of this added movement, active women had a higher abundance of health-promoting microbia including Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis and Akkermansia muciniphila, which–you guessed it–are SCFA-producing bacteria. Another study followed people beyond their new exercise regimens and found that on stopping exercise, their gut profiles reversed back to what it was before. This means that the key to gaining the benefits of exercise lies in a sustained, consistent exercise routine.

It is also important to note that excessively intense or extremely long periods of exercise, such as an ultra-marathon, can have negative impacts on gut health. Exercise intensity can be measured by your heart rate during your workout, which can be tracked by a fitness watch or other wearable or by briefly counting it yourself. However, this doesn’t mean that pursuing these types of intense exercise is all bad. Research has shown that the body’s long-term adaptations outweigh this temporary stress. Further, probiotic supplementation could help to offset these effects for athletes who participate in high levels of exercise. This is consistent with the well-documented concept of exercise as a hormetic stressor, which is a term that describes the phenomenon of a small dose of negative stress generating a beneficial, positive response. Maintaining a balanced approach to fitness is key to optimizing the gut-muscle connection.

How does our microbiome affect our ability to exercise?

The health and makeup of your microbiome also affect your athletic performance. If you have a dysbiotic microbiome, it can have a decreased ability to produce SCFAs which are very important to exercise performance. As we discussed above, SCFAs are not only beneficial for their anti-inflammatory effects, they are also an energy source for both your muscles and your intestinal cells. Surprisingly, SCFAs can contribute up to 10% of our daily caloric energy requirements so a decrease in production could significantly affect our available energy. This can lead to symptoms of fatigue, which can reduce your ability to exercise.

The gut microbiome also plays an important role in muscle recovery. Muscles require protein for muscle turnover and maintenance, and many gut microbes modulate protein metabolism. Microbes like Bacteroides, Propionibacterium, Streptococcus, Fusobacterium, Clostridium and Lactobacillus species are responsible for protein breakdown and metabolism and can be decreased in dysbiosis. Without adequate levels of these microbes, your gut might not be as efficient at breaking down proteins to use them to repair your muscles, prolonging recovery time.

The gut also plays a role in the function of two important metabolic pathways that regulate muscle cell growth – mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) and AMPK (adenosine-monophosphate activated-protein kinase). These pathways modulate muscle growth and breakdown by activating a series of enzymes and proteins in response to available nutrients, which are influenced by your microbiome. The function of these pathways affect your body’s ability to respond to and get stronger from exercise and relies on nutrients from your gut to function optimally.

Finally, a recent study found that certain bacteria in the gut can increase the levels of neurotransmitters responsible for motivation and reward, such as dopamine and serotonin. This could lead to an increased desire and motivation to exercise and experience the "feel-good" effects of physical activity. If your gut is unbalanced, this can affect your motivation to exercise and impair your overall performance.

How can I use this to maximize my exercise performance and gut health?

Consistent, moderate exercise is a vital part of a healthy gut. Aim to keep ~80% of your workouts at a moderate intensity, meaning 50-70% of your maximum heart rate. For example, this would mean running at a pace where you can hold a conversation. Start your exercise plan by setting realistic goals and gradually increasing the intensity and duration of your workouts. Find activities that you enjoy and that fit into your schedule, whether it's going for a jog in the morning, joining a fitness class after work, or taking a walk during your lunch break. Every little bit counts! If you can only commit to 10 minutes, do that and work your way up. Try to make exercise a priority by scheduling it into your day and treating it like any other important appointment. Don't forget to listen to your body and give yourself rest days to prevent overtraining. Over-exercising can harm the gut microbiome, so it’s important to remember that balance is the key here.

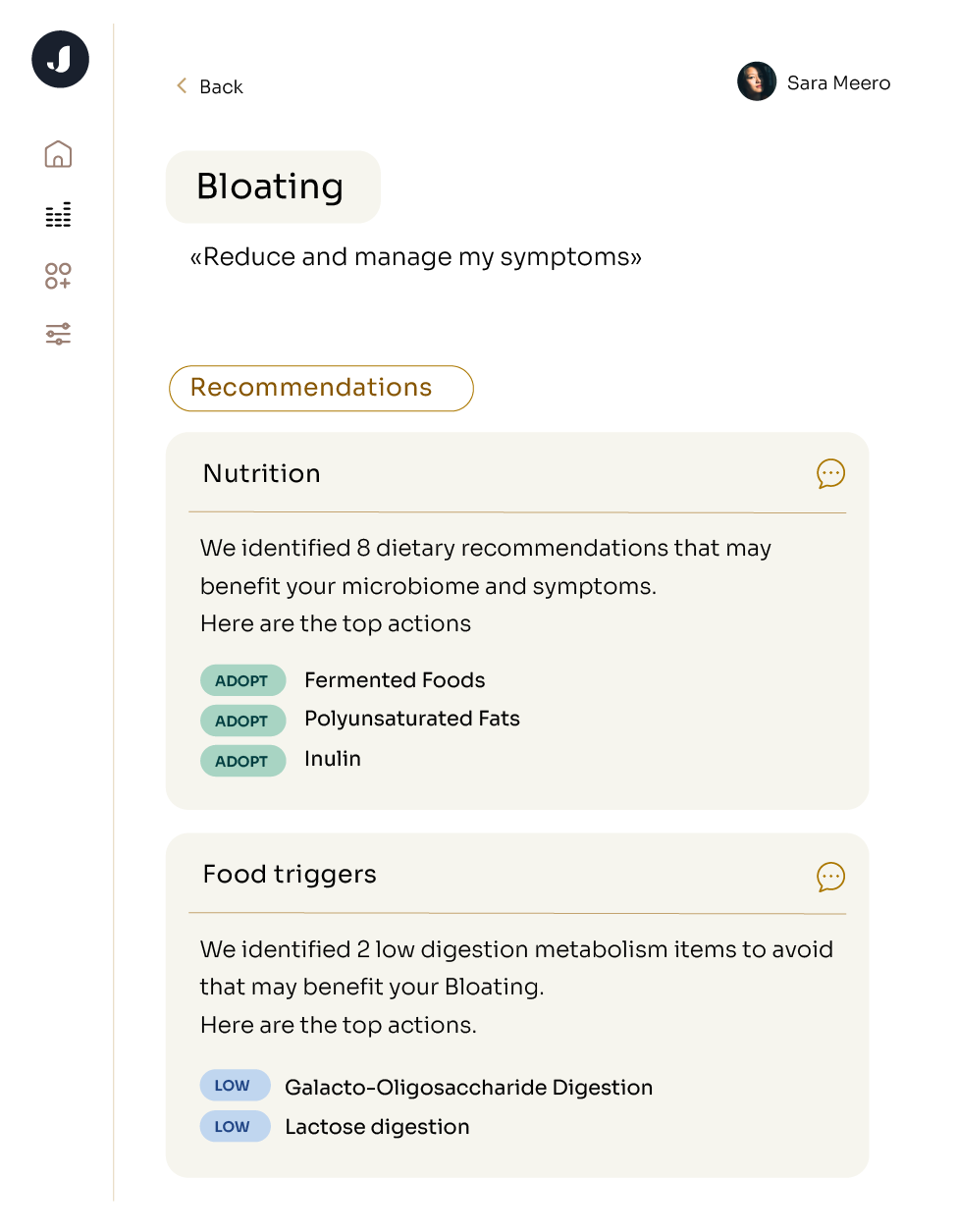

If you find that it’s harder to do exercises you could once do or that you have any of the above experiences of worsened athletic performance, it might be time to consider whether your gut health is contributing. Because everyone’s gut microbiome is unique to them, we recommend getting a personalized profiling kit to see which microbes might be contributing to your symptoms. This will help you tailor your dietary, supplement, and lifestyle changes to target exactly what is going on in your gut. If you want to start with some lifestyle changes in the meantime, check out our article on 10 Ways to Improve Your Gut Health.