FSA/HSA Eligible. Free Shipping, Always.

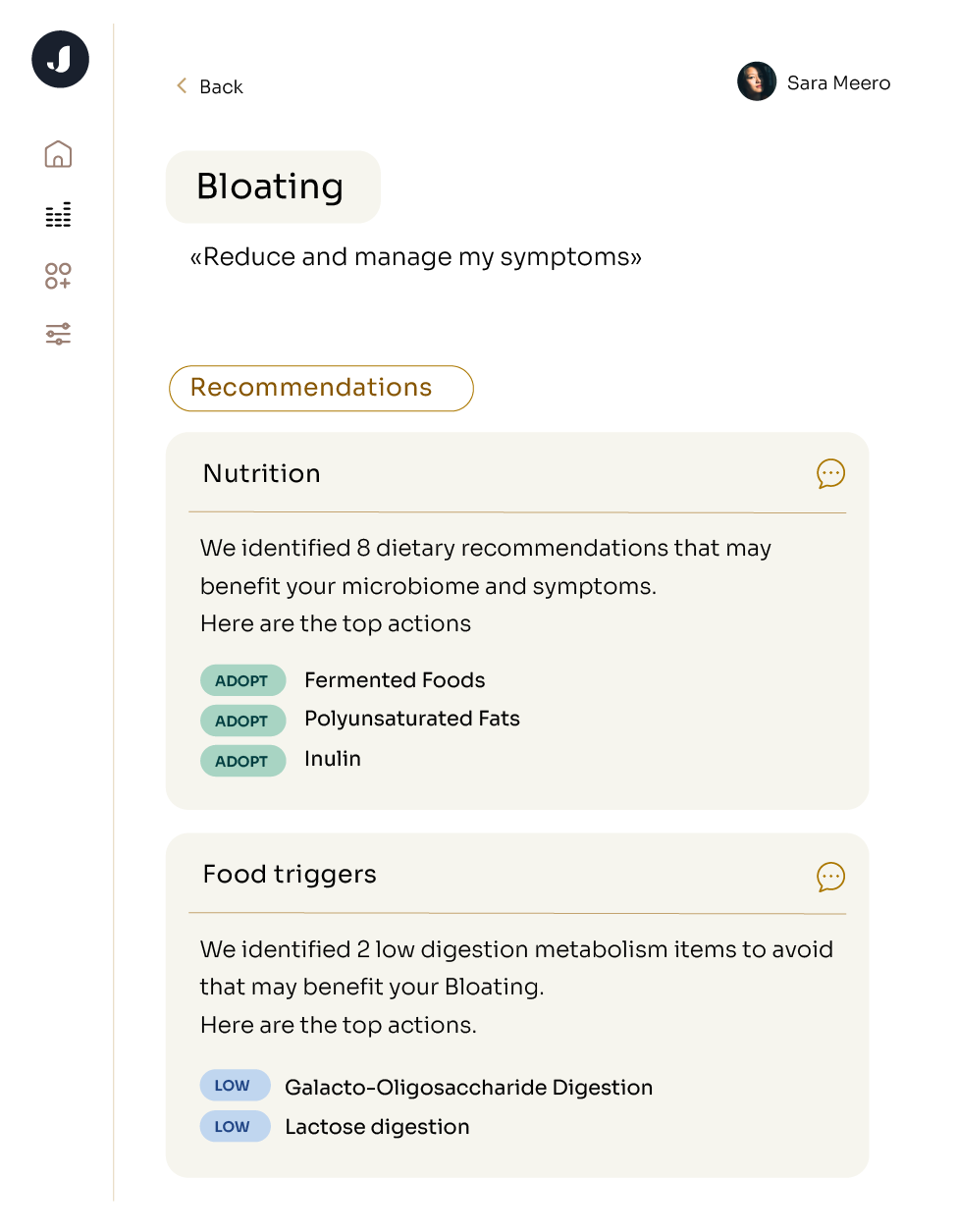

Diet + Nutrition

Gut-Brain Axis

IBS

Longevity

microbiome

Mood

10 Reasons To Test Your Gut Microbiome

Discover what gut microbiome testing is and why it's useful for evaluating your health risks