Alcohol consists of many different components that need to be broken down by the body. When gut bacteria break down substances, including alcohol and other compounds, they produce metabolites as a natural byproduct of this process. These metabolites have signaling functions between the other areas of the microbiome, the blood, and the liver, allowing them to move throughout the body. A common metabolite produced by this alcohol breakdown process is acetaldehyde, a highly toxic substance and known carcinogen. In conditions like pancreatitis, alcohol consumption and its breakdown can damage the pancreatic ducts, leading to a buildup of digestive enzymes within the pancreas. This buildup triggers pain and inflammation, hallmarks of pancreatitis.

Leaky gut is something frequently discussed here at Jona (see our earlier blog post), as it is connected to a slew of gut microbiome-related conditions. Although there is no “clear” line for what exactly constitutes leaky gut, it is known that the toxic disruption caused by the consumption and subsequent breakdown of alcohol can be a leading cause. More harmful bacteria can proliferate and “eat away” at the mucosal lining of the intestines increasing permeability, and allowing those toxic metabolites into the bloodstream. Additionally, some studies suggest that the translocation of bacteria from the gut to the liver can even cause liver diseases.

While much of the recent discussion has focused on the carcinogenic effects of alcohol, it’s important to include the role of your gut in this conversation. The ethanol component of alcohol is what is considered the true carcinogenic component, due to its ability to cause DNA damage. However, it also aids in the increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are produced by the guts epithelial and immune cells. At low to moderate levels, these ROS function as signaling molecules, promoting cancer cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and even drug resistance.

Several studies explore the impact of alcohol on gut microbiota composition in humans, highlighting significant shifts in microbial populations. One study found that chronic alcohol use in humans led to dysbiosis, with an increase in the Proteobacteria phylum, particularly the Gammaproteobacteria class, and a decrease in the Bacteroidetes phylum. Specific alterations included a rise in Bacilli and a decrease in Clostridia within Firmicutes. These microbial changes were associated with high serum endotoxin levels, suggesting a link to intestinal permeability and inflammation. In cirrhosis patients, Another study observed similar patterns, with increased Proteobacteria and Firmicutes and a notable enrichment of the Prevotellaceae family in alcoholic cirrhosis patients, compared to healthy controls and those with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis.

A third study investigated the effects of alcohol types, specifically red wine, dealcoholized red wine, and gin, on gut microbiota. Certain genera such as Enterococcus, Prevotella, and Bifidobacterium, and species like Bacteroidesuniformis and Blautia coccoides-Eubacterium rectale, were notably higher with red wine and dealcoholized red wine, potentially indicating prebiotic effects due to polyphenol consumption. Wine, especially red wine, is associated with significant histamine release. Red wine affects histamines significantly more than white wines - in fact, red wine generally has between 20–200% more histamine than white wine. That said, all wines are different and levels can vary between vintage, type, and fermentation process. The histamine concentration is significantly higher in red wine than in white wine because red wine is often fermented on or with seeds and skins which means they have higher levels of tannin (another potential irritant) which also creates more histamine. Conversely, gin consumption had a less pronounced effect on gut microbiota.

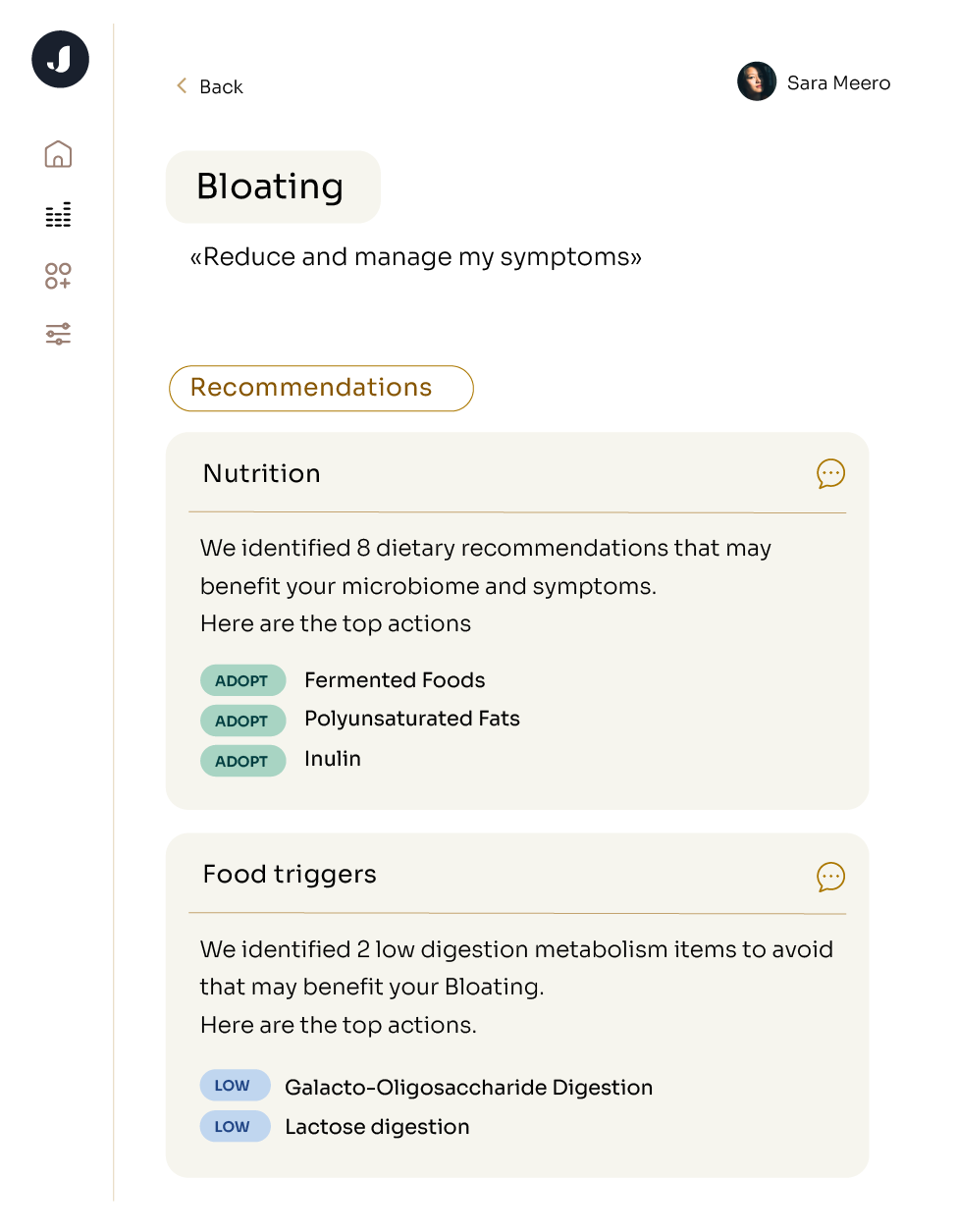

New year, new you, new gut. Understanding your body's science is essential—let a "gut-first" approach be your guide. While the other health benefits of dry January are often discussed, it's also a great way to give your gut some extra love. By reducing or eliminating alcohol, you give your gut a chance to heal, reducing inflammation, permeability, and even cancer risk. It doesn’t have to end on January 31st either.