What are probiotics?

Probiotics refer to living microorganisms capable of benefiting your health when consumed (source). Similar to a calcium supplement for bone strength, or iron for anemia, probiotics come in many different formats and combinations to address various health challenges. However, unlike a vitamin or mineral, probiotics are alive. The bacteria in probiotics can colonize your gut with beneficial microbes, help break down particular foods, and churn out metabolites, or digestive byproducts, that impact multiple body systems. Current research estimates that the average human gut holds about three pounds’ worth of bacteria, mostly in the large intestine, which help to break down and absorb all the food we eat (source). The sum total of interactions between each of these species and their human host comprises the gut microbiome, and like other ecosystems in nature, even slight disruption to the balance of its species can cause magnified effects. Probiotics can help restore microbes that have been depleted and could be beneficial to certain people in certain circumstances.

To keep up our vitamin and mineral analogy, probiotics come packaged in different ways. Many are found in foods, particularly in fermented products like yogurt, sauerkraut, and kimchi. In general, incorporating fermented foods into your diet can maintain an appropriate balance of bacteria and support healthy digestion. However, if you don't have access to these items, or you’re looking to use probiotics to target a particular health concern, you may want to consider a supplement.

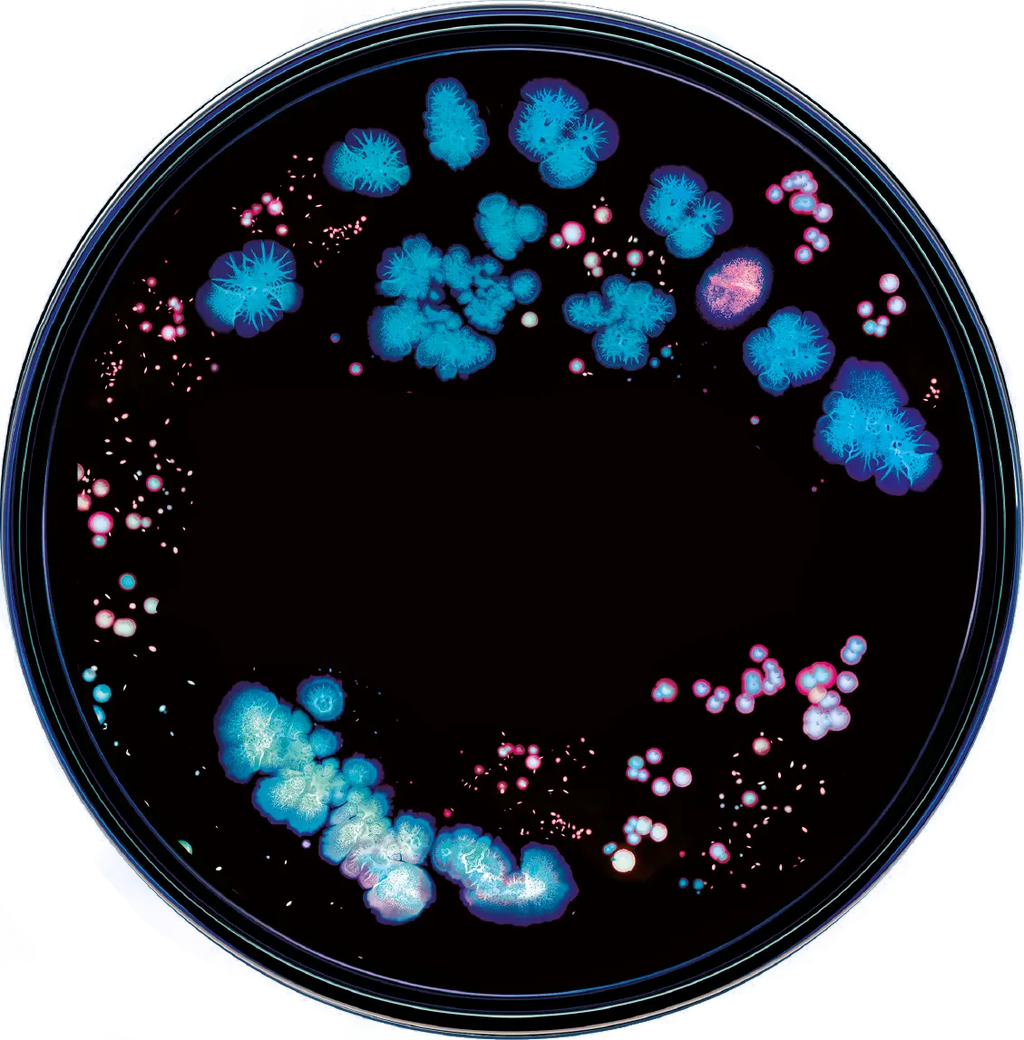

Nutrition scientists are still researching the various pros and cons of acquiring probiotics through food vs. supplements. Food sources tend to supply other nutrients alongside the probiotic, but supplements may offer a more concentrated or more bioavailable dose. Another thing to keep in mind: when it comes to probiotics, a little goes a long way. Typical probiotic doses are between 1 and 10 billion CFUs (colony-forming units, a measure of bacteria count), and taking extra may cause more harm than good (source).

A final note on probiotics: while various scientific organizations have advocated for their safety, probiotics are considered a supplement, not a drug, by the US FDA and consequently are subject to fewer regulations (source). Products advertised to ‘support gut health’ or ‘promote digestive comfort’ may not be scientifically validated in the US either with clinical trials or with in vitro studies, as the FDA doesn’t consider these to be health claims. In this article, we’ll share some of the current research to keep you up-to-date on the science.

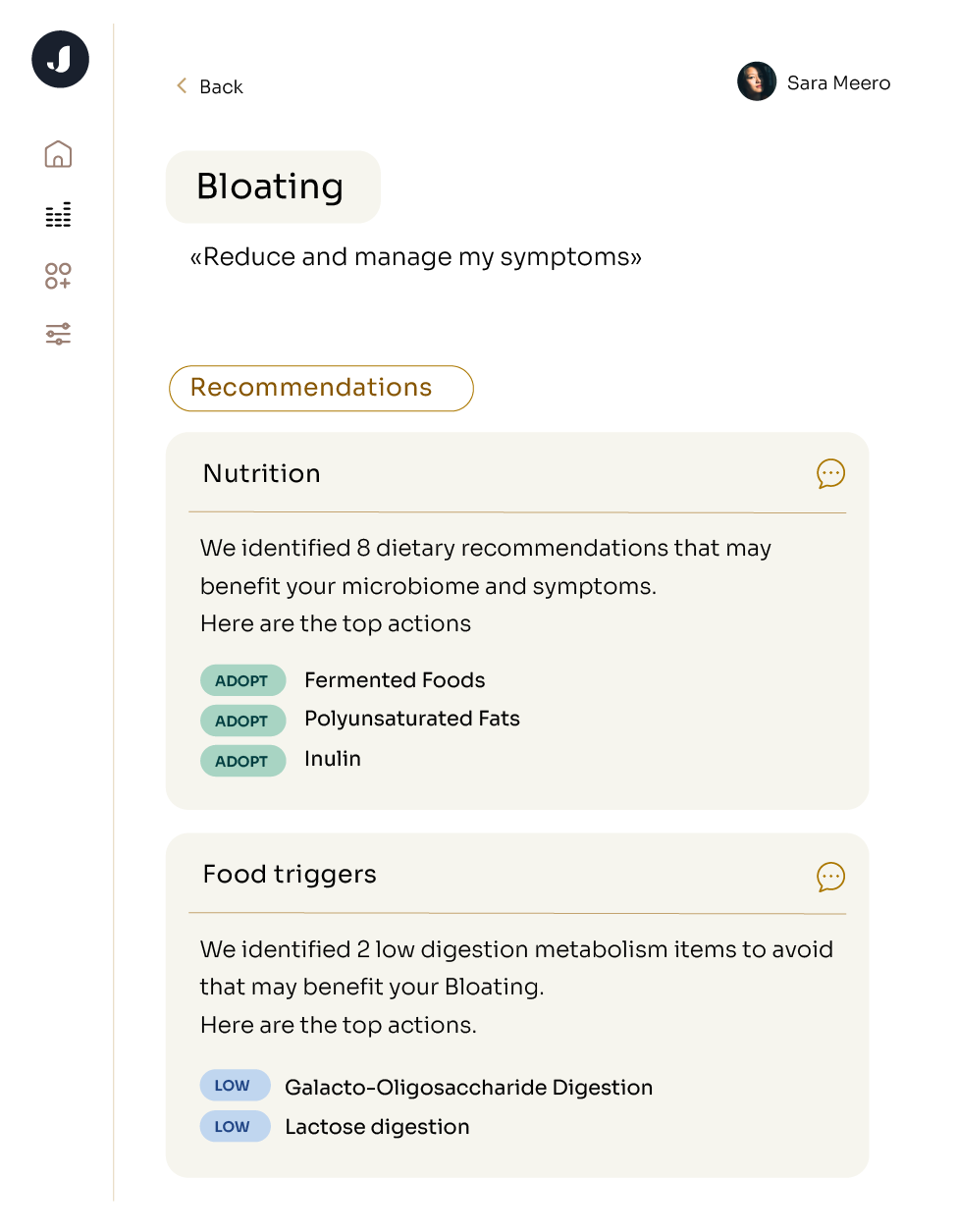

With so many versions on today’s pharmacy shelves, personal microbiome sequencing can identify which strains are most relevant to you. Jona does not manufacture or endorse particular supplement brands and the purpose of this blog is purely educational.

Some of the most common genera used in bacteria in today’s probiotics are Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Saccharomyces, Akkermansia, Streptococcus, Enterococcus, and Bacillus (source). Let’s go through each genus, including their applications and the research supporting their use.

Common Probiotics

LACTOBACILLUS

You might consider Lactobacillus if:

-

You’re lactose intolerant - Lactobacillus breaks down the lactose found in dairy products

-

You’re worried about stomach bugs - Lactobacillus may help you avoid getting sick by reducing intestinal pH and making your gut environment less hospitable to pathogenic bacteria (source) and outcompeting pathogens for binding space on the intestinal walls (source)

-

You want to lower your cholesterol - Lactobacillus has been shown to serum cholesterol levels (source)

Look for these species: Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. brevis, L. casei, L. rhamnosus

Research into Lactobacillus has shown potential applications in decreasing epithelial inflammation (source), improving symptoms of lactose intolerance, reducing types of diarrhea, particularly in children or for travelers’ diarrhea (source) and reducing incidence and severity of colon cancer (source).

BIFIDOBACTERIUM

You might consider Bifidobacterium if:

-

You’re worried about anxiety, depression, or cognitive decline - A combination of B. longum and L. helveticus decreased healthy participants’ anxiety and depression scores (source), and other Bifidobacterium species were shown to improve even major depressive disorder (source). B. longum also improved cognitive function in healthy older adults (source)

-

You have trouble digesting fruits and vegetables - Bifidobacterium are a key species breaking down tough plant fibers in the gut

-

You are lactose intolerant (source) - When taken with Lactobacillus casei, Bifidobacterium breve was shown to decrease symptoms of lactose intolerance. Interestingly, the benefits continued for a few months after participants stopped taking the probiotic!

Look for these species: B. breve, B. infantis, B. animalis, B. adolescentis, B. longum

At Jona, we’re particularly excited about the potential that Bifidobacterium has shown to improve anxiety, depression, and other mental health concerns via the gut-brain axis (source, source). They’re very robust to the harsh bile salts of the human GI tract, allowing them to outcompete other, weaker bacteria (source). Bifidobacterium species have been linked to improvements in constipation (source); reduced severity of diarrhea of various kinds, including travelers’ diarrhea (source), antibiotic-associated diarrhea (source), and radiation-induced diarrhea (source); and lowered cholesterol levels via their interactions with bile salts (source).

SACCHAROMYCES

You might consider Saccharomyces if:

-

You’re dealing with a bout of diarrhea - They are excellent at reducing diarrhea with limited side effects (source) and can help restore the balance of bacteria in your gut after your illness has passed (source)

-

You have IBD or increased intestinal permeability - S. boulardii positively impacts levels of a signaling molecule called E-cadherin that helps maintain intestinal permeability. E-cadherin signaling is often disrupted in IBD patients (source)

-

You want to boost your immune system - S. boulardii stimulates the production of T cells, a key element of the immune system (source)

Look for these species: S. cerevisiae var. boulardii

Saccharomyces species are a kind of fungal bacteria called mycobiota. They are excellent at reducing diarrhea with limited side effects (source). They’re also showing early promise for reducing symptoms of Crohn’s disease (source), IBS (source) and ulcerative colitis (source), but definitive evidence has yet to be shown in clinical trials.

AKKERMANSIA

You might consider Akkermansia if:

-

You want to maintain a healthy weight - Akkermansia muciniphila was associated with a smaller waist-to-hip ratio and healthier body fat distribution in adults restricting calories to lose weight (source)

-

You have bowel inflammation or increased intestinal permeability - Levels of A. muciniphila are diminished in patients with IBD and Crohn’s. The bacteria helps to protect the mucus layer of your GI tract, reducing irritation and strengthening the intestinal barrier (source, source, source)

Look for these species: A. muciniphila

Akkermansia muciniphila helps regulate the gut mucosa barrier. Its associations with weight loss are preliminary but promising (source).

STREPTOCOCCUS

You might consider Streptococcus if:

-

You want to protect your skin from aging - Eating S. thermophilus was found to increase collagen production in the skin and produce hyaluronic acid (source)

-

You’re looking to reduce soreness after exercise - S. thermophilus was found to help athletes recover more quickly after strenuous workouts (source)

-

You want to upregulate genes that reduce inflammation - S. thermophilus decreases several inflammation markers and regulates immune function (source)

Look for these species: S. thermophilus (found in yogurt)

Streptococcus species are more fragile than other probiotic species and may be less able to tolerate the chemical environment of the gastrointestinal tract, although some controversy exists regarding the way we measure bacterial survival through the GI tract (source). As of now, the best-tested source of S. thermophilus is yogurt.

ENTEROCOCCUS:

You might consider Enterococcus if:

-

You’re worried about infection - Enterococcus produces bacteroicins, which antagonize the growth of pathogenic bacteria and mold (source, source)

Look for these species: E. faecium

Enterococcus species, particularly E. faecium, have been shown to reduce antibiotic-associated diarrhea (source). However, E. faecium can be resistant to some antibiotics including vancomycin, so there is a lack of consensus on its proper use (source).

BACILLUS

You might consider Bacillus if:

-

You want to reduce inflammation and risk of infection - Bacillus can have a calming effect on the GI tract, especially after H. pylori eradication therapy (source). B. clausii has been shown to antagonize the growth of infectious bacteria by secreting a substance called coagulin, which combats pathogens in the GI tract (source, source)

Look for these species: B. subtilis, B. clausii, B. subtilis, B. polyfermenticus

Bacillus species show promise for reducing antibiotic-associated diarrhea (source) as well as bacterial vaginosis (source) and infections of H. pylori, the bacteria that causes ulcers (source). The Japanese food natto, produced from fermented soybeans, is a good source of B. subtilis, and B. polyfermenticus is found in kimchi.